One of the mistakes we often make when discussing totalitarianism is assuming that those within the system do not believe in the tenets of said system. Often, this is because we believe our own propaganda. Consider, for example, North Korea. When thinking about what life must be like for an individual living under that regime and within that structure, it is commonplace to assume that everyone knows they are living in a broken system and remain silent due to fear.

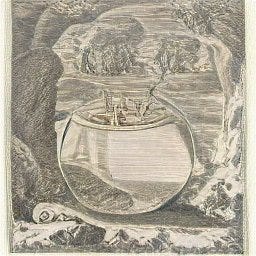

We saw our superstition manifest itself in the last decade when Kim Jong-il died. At the time, many in the western media speculated that North Koreans were faking their grief. Yet, we are on the outside of the fishbowl, and for decades the best view into the thoughts of those on the inside have come from biased accounts from defectors. However, while fear may play a part, it is more likely that there is a spectrum of opinions in North Korea that includes a sizeable base of true believers. On the inside of the fishbowl, it is difficult to think in alternatives.

That’s what makes this article in the New York Times so bloody fascinating. The author lays out his interpretation of the American political landscape in the modern era. He divides the parties into two camps, the pro-democracy types (his tribe) versus the fascists (any other tribe). Needless to say, he believes the failings of his tribe are their rigid focus on policy, with too many arguments build on facts, figures, and logic. Juxtaposed to this is the view that the other tribe specializes in cynical attacks and “meaning making” done “for their own dark purposes”.

The author presents a grand strategy for his tribe to correct themselves that includes weaving better stories and becoming slightly more ‘inclusive’ by “making space for the still waking” as long as those individuals in all of his tribes deal breaker issues. Obviously, it is clear which tribe any writer who writes for the New York Times belongs. They call themselves the left, and I doubt anyone outside that tribe’s fishbowl would say their biggest weakness is a rigid focus on policy, facts, figures, and logic. Nor does the side with an ideological structure that is full of deal-breaker issues sound particularly pro-democracy.

Back to our North Korean example, the regime in that country also calls themselves democratic, and the citizens in that country have a constitution not unlike those in many western nations. But they are ideologically rigid. There are things that people there simply cannot do = deal breakers that, if violated, would harm an individuals ability to continue to exist within the system. Calling oneself pro-democracy does not mean they believe in the tenets of democracy.

In fact, the old paradox of democracy, levied by Richard Wollheim, arises when a ‘democrat’ believes choice A ought to be the case, yet the ‘democratic machine’ (the will of the majority) believes choice B ought to be the case. The democrat must believe, then, in both choice A (by virtue of personal choice) and choice B (by virtue of being a democrat). If these choices are in conflict, then a paradox arises.

The “pro-democracy” types on the left are rabidly against anything that does not fit into their tribe’s ideological structure, which they call fascism without ever defining the word. Within the fishbowl, however, they cannot see that a paradox exists. In the same way they use the word fascism to describe anything not in their ideological structure, they use democracy to describe anything within it. For the left, the definition of democracy is just as unimportant as it is in North Korea.

Counter to what our New York Times author says, his tribe’s ideological structure is not born out of policy, facts, figures, or logic. Most of their policy is based on fiat. The famous example in the US is Obamacare, but the pandemic showed us just how far they are willing to go with making policy by fiat. Even when they approach policy using traditional means, as with the Inflation Reduction Act, facts, figures, and logic are nowhere to be seen. Indeed, it would be a strange coincidence that the key to reducing inflation is a grab bag of items from the left’s wish list packaged together into an enormous spending bill.

We are about to see the perfect example of how unimportant democracy is to these people on November 8th. For example, six states are voting on issues addressing one of the left’s deal-breaking issues in abortion. It is a pretty safe assumption that at least one of those democratic votes will go against leftist ideological structure, and when that happens, they will, as per usual, take to the streets (likely violently) against the result. The fact that it will be a result of a democratic process will be an obvious contraction.

But it would be a mistake to assume that obvious contradictions are obvious to those living in the fishbowl. If you spend some time around these people outside of the Twittersphere, you’ll find that they are not being disingenuous: they are simply true believers. In a way, that’s what makes them so dangerous.

Great post. For a few years now, I've been thinking the electoral American left is very much a Vichy party. They would refuse to work with anyone outside the party—they're true believers, as you make clear—even if it meant the country would lose a war and suffer enduring consequences. Not necessarily occupation, but possibly loss of territory and a humiliating, costly condition of surrender.

Great analysis and summation; being so brief without leaving important points out is also a sign of great thought having been put in.

Yes, doublethink is necessary to resolve the paradox, conscious doublethink at that. The Party is right when it claims 2+2=5, and 2+2=4 at the same time: to be able to think like that is a prerequisite to belonging to the modern (post-1970s) general Leftist cluster of ideas. To be able to think like that consciously without rationalisation or continuous real-time editing of memory is a prerequisite of achieving a career, even leadership, in the same Left.

Or to sum it up: Lenin was a genius when it comes to understand how perception and communication creates, uncreates and recreates reality in the mind.