This is an expansion of the Guide to an Evil Empire: Pfizer Lawsuit article. Due to the sheer size of this article, I will break it into pieces for easy reading. As always, I have attempted to be as accurate as possible, but if there are issues or nuances I have missed, please feel free to leave a comment and I will make a correction. Pfizer has been involved in more lawsuits than I can count, so I attempt to use individual lawsuits as examples of their business practices. The goal of these articles is to make the most extensive and exhaustive account of the long history of the Pfizer empire. Please like, share, comment, and subscribe if you enjoyed this content.

The 1970’s to the year 2000 was the era of expansion for Pfizer. Many of their most well known product lines were launched, from Advil to Lipitor. Notably, though, more infamous drugs like Feldene to Trovan also made their debut. Their full catalogue became immense1 and acquisitions, for better or for worse, further diversified their holdings.

And with expansion came the increasing drive for ever-more profits. As such, Pfizer's drive to grow brought many well-publicized scandals.

Bribery abroad

While this may not be the first instance of Pfizer bribing foreign government officials, this appears to be the first time they were caught. No. This is not the more recent example that I expounded upon in the original Guide to an Evil Empire. This case, in fact, dates all the way back to 1976. An internal Pfizer investigation found three instances of “questionable or perhaps illegal payments”, which totaled $265,000 including a $22,500 contribution to a foreign trade commission.

The fact that this was the result of an internal investigation suggests that, at this point in time, this was likely not yet standard practice in the company or there was pressure from regulators to perform such an investigation. Still, the culture within the corporate superstructure was clearly decaying. If this internal investigation could be seen as a sign of accountability, to some degree, it may have been the last sign the company would see for a long time.

Heart complications

In 1976, a company named Shiley developed the Bjork-Shiley Convexo-Concave heart valve. This company was acquired in 1979 by Pfizer and the valve hit the market. Over 55,000 heart valves were installed in patients by the mid-1980’s, but the heart valve had a major defect: “the outflow strut on the metal alloy valves was prone to fracture, enabling blood to flow unimpeded and causing heart failure”.

The FDA allowed the heart valve to stay on the market for seven years before removing it. It was not until four years later, in 1990 and under the pressure of a growing public scandal, that Pfizer sent letters to medical doctors that installed the valves informing them of the danger. At least 300 people died from the faulty heart valves by 1992. Investors feared that the fallout from the defective heart valves could cost up to $5 billion to resolve, and, indeed, the allegations of fraud likely caused fear of jail time within the upper brass of Pfizer. The director of the Public Citizens’ Health Research Group believed that criminal charges should have been brought against the company.

In the end, the company ended up resolving the class action suit against them in 1992. The resolution $215 million, including paying for ongoing medical consultations, further research into the issue, and a small payout to each heart valve recipient. All together, this seems like a lackluster payout for the damage done, and a true slap on the wrist for hundreds of deaths. The question in this case was not whether Pfizer’s product was faulty; rather, their reaction to the product defect. If Pfizer had acted promptly after the product was removed from the market, say, then this scandal would not have been as bad. They did not. They waited for years after the incidence before mounting a proper response leading to hundreds more individuals dying in the meantime. If there were signs of corporate accountability during the bribery scandal, by the 1990’s, any semblance of accountability had long since vanished.

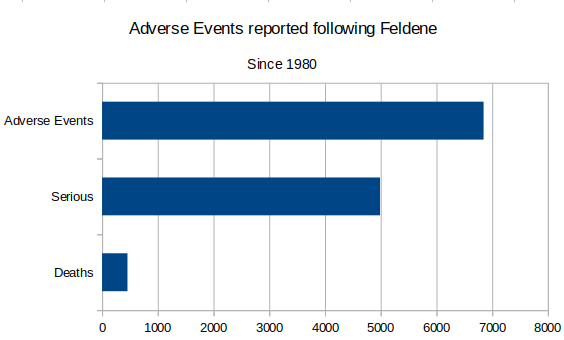

Feldene

At the same time as the scandal surrounding the malfunctioning heart valve, a new scandal was erupting. Feldene was a popular arthritis medication regularly prescribed in the 1980s. There have been many adverse events following use of this drug. One of the most commonly cited complications is gastrointestinal hemorrhages.

In 1988, an article from The Multinational Monitor noted that a letter was sent to the FDA by Public Citizen's Health Research Group, including documents that “provide evidence that Pfizer withheld knowledge of deaths and other serious adverse reactions in overseas users of Feldene until after the FDA approved Feldene for U.S. patients in April, 1982”. No action was taken by the FDA to address this issue.

As the article noted, “[t]he average consumer should take a close look at the package. If it says Pfizer, stay away.”

Advil

The public did not take this warning to heart, though. Originally released in 1984, one of the most commonly used drugs on the market is Pfizer’s Advil. Advil can be found in cupboards across the world; in fact, you or someone in your inner circle definitely has either purchased or taken Advil. Considering the sheer volume of use associated with this drug, the adverse event rate is actually quite low, but that does not mean there have not been cases where consumers have had bad reactions to the drug.

There have been 74 reported cases of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and 40 cases of Toxic Epidermal Necrosis. As discussed in my original Guide to an Evil Empire article, “one such case involved a teenager that had severe blistering over 35% of his body, resulting in essentially no skin on his face, neck, scalp, trunk, back, buttocks, arms, and legs. As a result, the Plaintiff was left permanently disfigured and partially blind. Pfizer’s motion to dismiss the case resulted in a manufacturing defect claim being dismissed without prejudice; however, their motion to dismiss the claim of willful and wanton negligence was denied.

The amount of adverse reactions have consistently grown since the original release of the drug, and few people even consider that the drug may be dangerous in certain cases. As with any drug, though, there are risks and buyers should be aware.

More price fixing

With so many popular products being launched in the 1980’s and early 1990’s, one has to wonder why a company would need to further leverage their position to increase profit margins. Yet, the pharmaceutical industry is well-known for pushing every advantage afforded to them. Pfizer agreed, along with fourteen other pharmaceutical companies, to resolve a class action suit alleging that they conspired to fix the prices of drugs sold to thousands of independent pharmacies. The company paid $31.3 million as part of the $408 million deal made in February, 1996.

And even more price fixing

Just a few years later, in the late 1990’s, the Justice Department once again began investigating Pfizer for price fixing this time in relation to the food additive Maltol. The charge levied against the company was conspiring with a Maltol producer to allocate costumers and territories for sales, thus violating the Sherman Act in order to maximize profit. Pfizer agreed to pay $20 million in criminal fines in order to resolve this case.

Promoting drugs for off-label use

In the mid-1990’s the company distributed promotional material and a journal reprint for the unapproved use of Zoloft for depression after myocardial infraction. The FDA charged them for this, and noted that it raised significant safety concerns. Those safety concerns, ahem, included the fact that adverse events from Zoloft included a long list of heart issues including myocardial infraction.

Promoting drugs for off-label use is relatively commonplace in the drug industry, and indeed, we will see in a later article that Pfizer is a repeat offender in this sphere as well.

Testing deadly drugs on children in Nigeria

But even promoting drugs like Zoloft to at-risk groups pales in comparison to their actions in the latter half of the 1990’s. One of the more shocking, but probably not isolated, incidents was the Trovan experiments. In 1996, there was a meningitis epidemic in Nigeria. International relief efforts mounted and many organizations sprang into action. Pfizer, under the guise of going to Nigeria to help, used the opportunity to test their new meningitis drug Trovan.

Pfizer would later claim that regulators in the country gave them permission to use the drug in Nigeria; a statement contradicted by the Nigerian government and covered, and dismissed, in an expose by the Washington Post. A panel of medical experts in Nigeria would later call it “an illegal trial of an unregistered drug”.

The clinical trial was performed on 200 children without obtaining informed consent from either the parents or children. They were never told the drug was experimental. In order to make their own drug look better, Pfizer used ceftriaxone, the effective “gold standard” treatment, at a reduced dosage. Many of the children in the trial died or were permanently disabled, eventually leading to a $75 million settlement. In the aftermath, Pfizer would blackmail members of the Nigerian government; however, I will save that story for a later article.

Subsequently, in 1997, Trovan would be approved for use in the US market by the FDA; however, due to advocacy from groups like Public Citizen’s Health Research Group, the drug was quickly removed from the market due to severe adverse side effects including acute liver damage.

In only a couple of years on the market, there were 1520 severe adverse events and 65 deaths reported to the FDA despite meningitis being relatively rare in the US.

Price gouging in Africa

As the century wound to an end, the high-profile AIDS activist group “Act Up” targeted Pfizer specifically for price gouging in Africa. They noted that fluconazole, marketed by Pfizer as Diflucan, was sold for $4.15 a pill in South Africa and $18 a pill in Kenya, both places where Pfizer held monopoly power. In Thailand, where generic versions of the drug were available, the pill was sold for a mere 29 cents.

The drug treats cryptococcal meningitis, a particularly painful brain disorder that affects 1 in 10 AIDS patients. Here is a chart from Lancet showing the prices of capsules in countries where Pfizer did and did not hold monopoly power: Note, these numbers were collected after the Act Up campaign, so the prices in Kenya are lower and the prices in South Africa are higher.

I seem to recall global outrage when Martin Shkreli acted in a similar manner. In fact, he is sitting in a federal penitentiary for price gouging. His biggest mistake seems to have been not working for Pfizer.

The merger

Shortly after y2k, when the rest of the world was still celebrating the new century, a $90 billion merger between Warner-Lambert and Pfizer was announced. The merger, of course, was probably more of a hostile takeover, but the deal catapulted the new company into the second largest pharmaceutical in the world. The New York Times noted that under the direction of their CEO at the time, William Steere, selling drugs was like selling toothpaste.

Rezulin

Before their merger with Pfizer, Warner-Lambert brought the anti-diabetic drug Rezulin to the US market. During the clinical trials, those who received Rezulin had alanine aminotransferase levels at a rate three times greater than those who received the placebo. Before the drug even hit the market, John Gueriguian from the FDA warned of liver damage associated with the drug. His hypothesis was proven in the following years and the drug was removed from the market in the year 2000, after just three years on the market. The removal of the drug from the market came after and concerns from an FDA whistleblower warning of a growing list of deaths due to liver damage.

During one of the following lawsuits, the lawyer for plaintiff’s out of Michigan contested that Warner-Lambert (now represented by Pfizer as part of the merger) marketed a defective product and withheld information during the trials. In total, 35,000 personal injury claims were filed against the manufacturer. In 2001, Pfizer ended up paying $30 million to Margarita Sanchez for the drug causing her liver to fail. The bulk of the cases, however, would not be resolved until 2009 costing Pfizer around $750 million in total.

Rezulin may have been an example of Pfizer “making things right”, despite years of foot dragging, but the years following the Warner-Lambert acquisition show that these court cases were solved out of necessity, more than anything else.

This is the end of part two of a multi-part series. Part two covers the middle years of Pfizer’s corporate rise up until the the year 2000. Pfizer’s lawsuits get progressively more dense as the years go on but this may be due to better records being kept in the latter part of Pfizer’s history.

This list includes many of the products that would appear in lawsuits and scandals after the new millennium: Zyrtec, Zithromax, Viagra, Zoloft, Norvasc, Neurontin, Effexor, Protonix, Xeljanz, Bextra, Lipitor, Aricept, Tikosyn, and Celebrex.

Thank you for mentioning that Health Research Group. I have immediately signed up, and will read through more of the articles in the coming weeks !

Interesting how all these numbers of AEs pale in comparison with the savior of the world Covid vaxxes... And yet, here we are.